Executive Summary

Community outreach, while performed, did not shape the writing of the draft and failed to affirmatively further fair housing (AFFH).

The city does not make AFFH a focal component of its site inventory. We find glaring omissions of analysis with respect to school segregation and environmental justice, and the few gestures towards AFFH in the site inventory are insufficient to overcome patterns of segregation.

The city seeks to justify rather than address governmental constraints to housing production. We estimate costs imposed by city regulations add 26.4% to the development cost of a typical 800sqft unit. Furthermore, **typical apartment projects will remain infeasible unless development costs are reduced by over two hundred thousand dollars per door. **The draft insufficiently analyzes the following contributing constraints: \

- BMR in-lieu fees (9% of per unit cost)

- Park in-lieu fees (6-8.5% of per unit cost)

- Parking minima (8.4% of per unit cost)

- Permitting delays (3-6% of per unit cost)

- Staff Capacity

- Development guidelines

Only some of the above constraints are acknowledged as constraints by the current draft.1 Furthermore we have arrived at somewhat different levels of impact than the city’s analysis.

Appendix 1. Community Outreach Appendix

The core purpose of the housing element outreach is that the full community, especially those who are represented from populations that have been historically excluded and are at risk of displacement, are able to share their housing needs. Although the city has done a great job in terms of promoting the housing element outreach and making staff available, there is no connection between that outreach and to the housing needs, constraints and solutions in this draft. The city must demonstrate how the input from these stakeholder meetings and public meetings shaped the housing element draft, particularly to Affirmatively Further Fair Housing (AFFH). These meetings must be meaningful and frequent throughout the entire housing element process and source the housing needs and possible solutions from the targeted groups2. “This process is intended to demonstrate willingness to consider and incorporate stakeholder input. The public participation process should not be used to “rubber stamp” a predetermined objective or policy.”3

The Housing Element draft does not provide a summary of public comments and explain how the comments were considered and incorporated, including comments that were not incorporated. The draft Housing Element lists only a summary of comments received at the Virtual Community Workshop held on September 23, 2021 and through the Community Feedback Form. Neither of these are sufficient to address the process requirements laid out in the law or the HCD guidance document, let alone meet the higher standard required for AFFH outreach.

Subsequently, many of the policies and programs are incomplete not only in their lack of definition, explanation and timeline, but also are missing in recommendations suggested by impacted communities. We would particularly like to refer to program 2.5: Affirmatively Further Fair Housing as an example of a program that has no clearly defined actions or deadlines to reach its stated goal.

Appendix 2. AFFH

Spatial Segregation in Mountain View

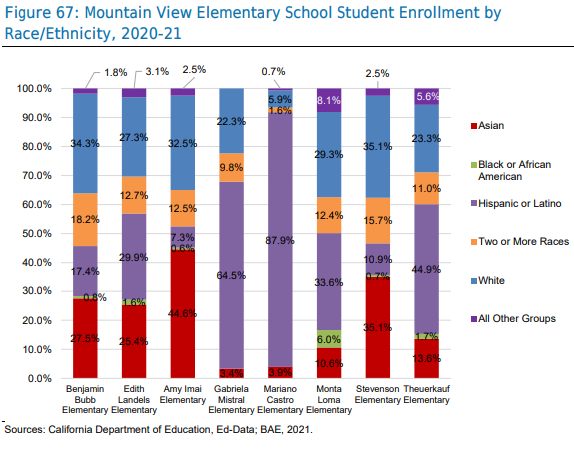

Mountain View’s current built environment still features substantial spatial segregation along racial and economic lines. The most extreme examples of this are made obvious by the racial diversity of our elementary schools, wherein Amy Imai Elementary, located in the Southeastern portion of the city, has a 7.3% Hispanic/Latino enrollment; but Mariano Castro Elementary has an 87.9% Hispanic/Latino enrollment in the central/western portion of the city (see Figure 67 in the Housing Element Draft). This is reflective of a long history of land-use choices that have led to multi-family housing—which allows for greater natural affordability than isolated single-family houses—being concentrated into particular neighborhoods and along a narrow corridor beside El Camino Real4. Unfortunately, the current site inventory largely perpetuates the land-use patterns that have led to our current levels of internal segregation.

Consistent with HCD guidance,5 the city should adopt clear metrics for tracking our progress towards improved integration and to commit to specific land-use policy changes in the upcoming Housing Element cycle to improve local integration and reduce spatial disparities associated with housing affordability. While the specific metrics would require some effort to pin down precisely, we would consider the below a reasonable starting point:

- Racial disparities between local schools.

- Median effective housing cost by census tract (with appropriate conversions for comparing the costs of renting vs. homeownership).

- Percentage of renters vs. homeowners by census tract.

- Clustering6 of multi-family residential zones within census tracts.

- Tracking rate of site inventory development by median income of the neighborhood/census tract, to ensure that changes to land-use regulations are actually being reflected in new housing developments.

And while exact policies to address these issues can vary, we urge the city to adopt concrete proposals to encourage future developments that improve the integration of our city.

Detailed Discussion on Spatial Segregation in Mountain View

This section goes into some more detail on the points discussed in the previous section, with some extra supporting references and copies of some of the key maps and charts from the Housing Element draft.

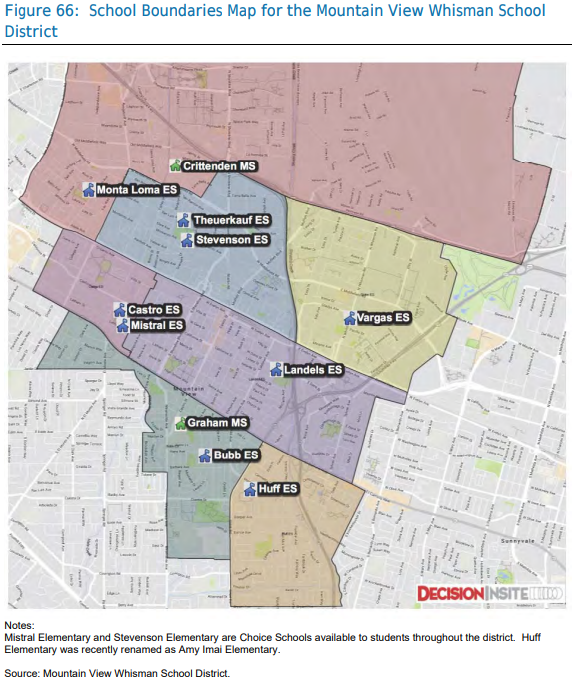

Firstly, referencing racial disparities in local Elementary Schools, the following is the current Elementary School boundaries (note that Huff has since been renamed to Amy Imai), from Figure 66 in the Housing Element Draft:

And the below diagram provides data and the racial makeup of each school’s enrollment:

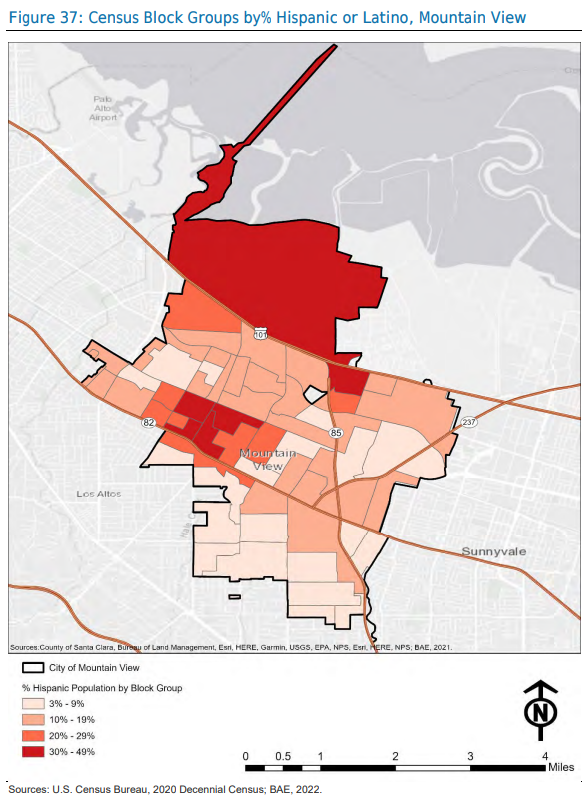

For additional reference, consider Figure 37 of the draft Housing Element showing the distribution of Hispanic/Latino population within Mountain View:

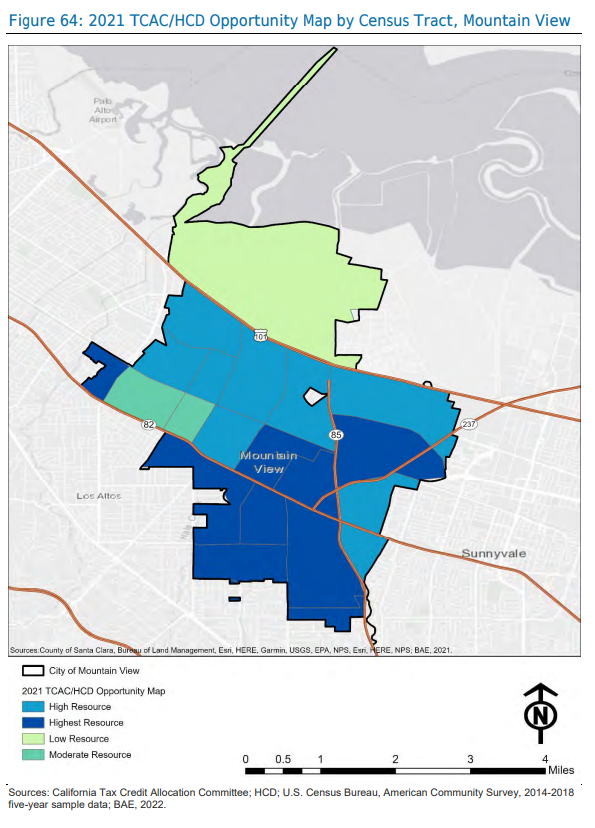

When compared to the HCD Opportunity Map (Figure 64 from the report), we can see that Mariano Castro’s catchment corresponds with the one “Moderate Resource” area in Mountain View, while Amy Imai Elementary corresponds almost entirely with “Highest Resource” areas, with Bubb (the second lowest Hispanic/Latino enrollment school with a regular geographic area—note that Stevenson is a “choice school”) consisting entirely of “Highest Resource” tracts:

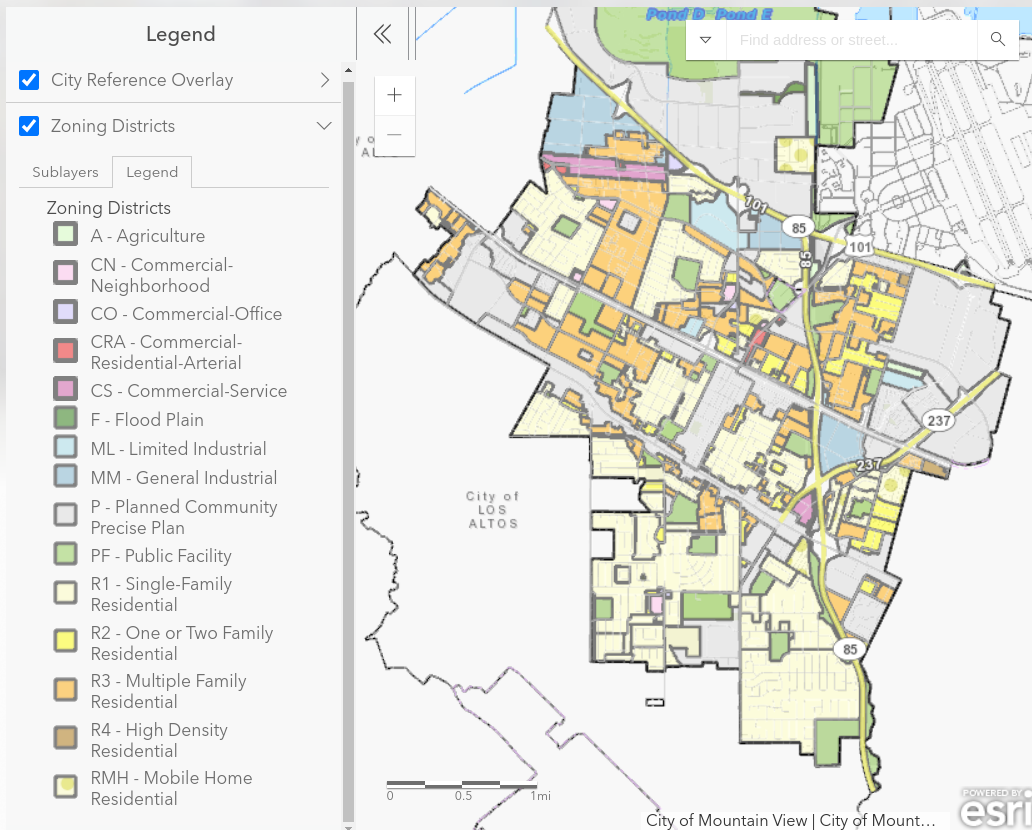

If we compare this to Mountain View’s current Zoning Map, we see how large tracts of Mountain View, particularly south of El Camino Real, still forbid multi-family residential developments. Of particular note is that Mountain View High School—the only public high school in the city7—is in the far Southeastern corner of the city, meaning that one of the highest resource, least affordable areas of the city is also the area of the city whose children have the safest and easiest access to the High School.

The main exception to this rule is the area in the immediate vicinity of El Camino Real (which is also likely the main reason Bubb & Amy Imai do not have even more extreme enrollment disparities). This forces people looking for housing at price-points below that of a multi-million dollar single family home into living immediately adjacent to one of the busiest traffic8 corridors in the city, with high levels of air pollution9, noise pollution10, and immediately along one of our highest injury corridors in the city11.

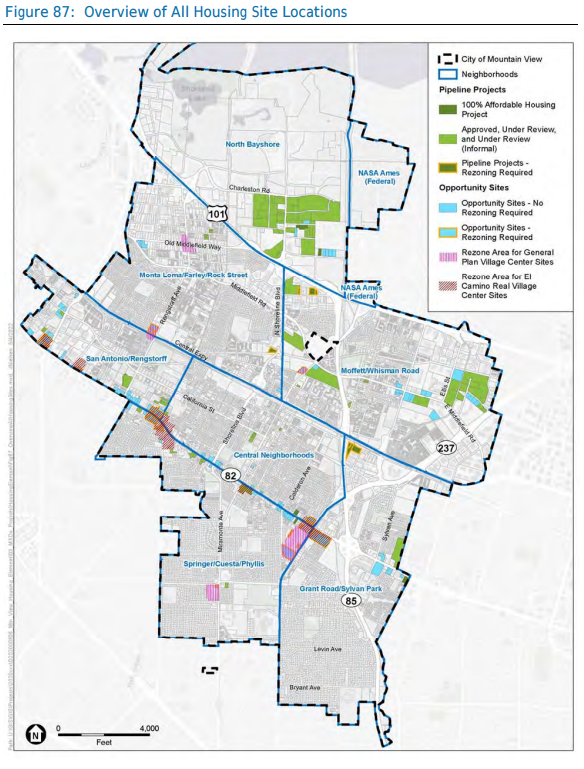

If we review the draft site inventory (Figure 87 from the draft Housing element), we see that it largely perpetuates these issues, leaving most of the southern portions of Mountain View unchanged, and outside the key pipeline projects in the North Bayshore and East Whisman areas (both of which have very little housing currently, beyond a mobile home park in North Bayshore), much of the site inventory is focused along parcels immediately along El Camino Real:

There are three main exceptions to this—the two village center sites south of El Camino, and the Cuesta Annex. While developing these would represent some movement in the right direction, focusing overly much on a couple of large sites still maintains the large neighborhoods of extremely unaffordable (and, by extension, exclusionary) housing. It should also be noted that attempts to use the Cuesta Annex site for a flood basin in the past met with intense local opposition and an attempt to build teacher housing at Cooper Park in the catchment area for Amy Imai Elementary met with such strong local opposition that the Mountain View City Council at the time chose to instead aim to build the housing as part of a larger project in a less-affluent and more diverse part of the city12. It is likely that any planned developments in these areas will meet with local opposition, and the city will need to have a plan to deal with it. This is why we propose tracking whether sites in more-affluent areas are being developed at a lower rate than those in the rest of the city.

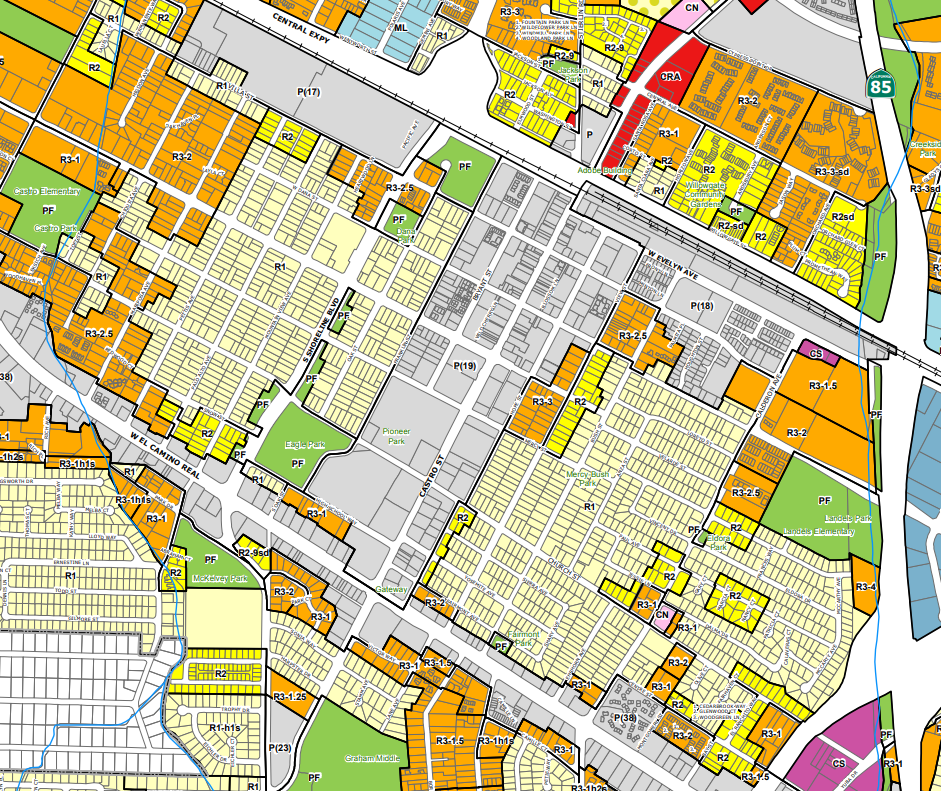

The other key area of Mountain View where existing land-use restrictions needlessly reduce availability of multi-family housing are some of the neighborhoods around downtown. For reference, zooming in on the zoning map from earlier:

This is arguably the highest amenity part of Mountain View, with the downtown transit center at the north end of Castro St, El Camino Real with Mountain View’s only frequent bus lines, and the entirety of the downtown area with its variety of restaurants, offices, and sundry retail. However, most of the land nearest downtown outside of the precise plan area itself (in gray), is currently zoned R1. While this is a less blatant example of spatial segregation than the neighborhoods south of El Camino Real (because the areas of R1 zoning are not quite so large), this still creates a bizarre situation where much of the densest and most affordable housing in the city (towards the top-left of that map, along California St) is actually farther from key amenities than lower-density housing, which unnecessarily increases the travel time for commutes, errands, and leisure trips for people who cannot afford a single-family home. Currently, none of the R1 areas between El Camino Real and Central Expressway in that view are planned for any additional housing as part of the site inventory.

Appendix 3. Constraints

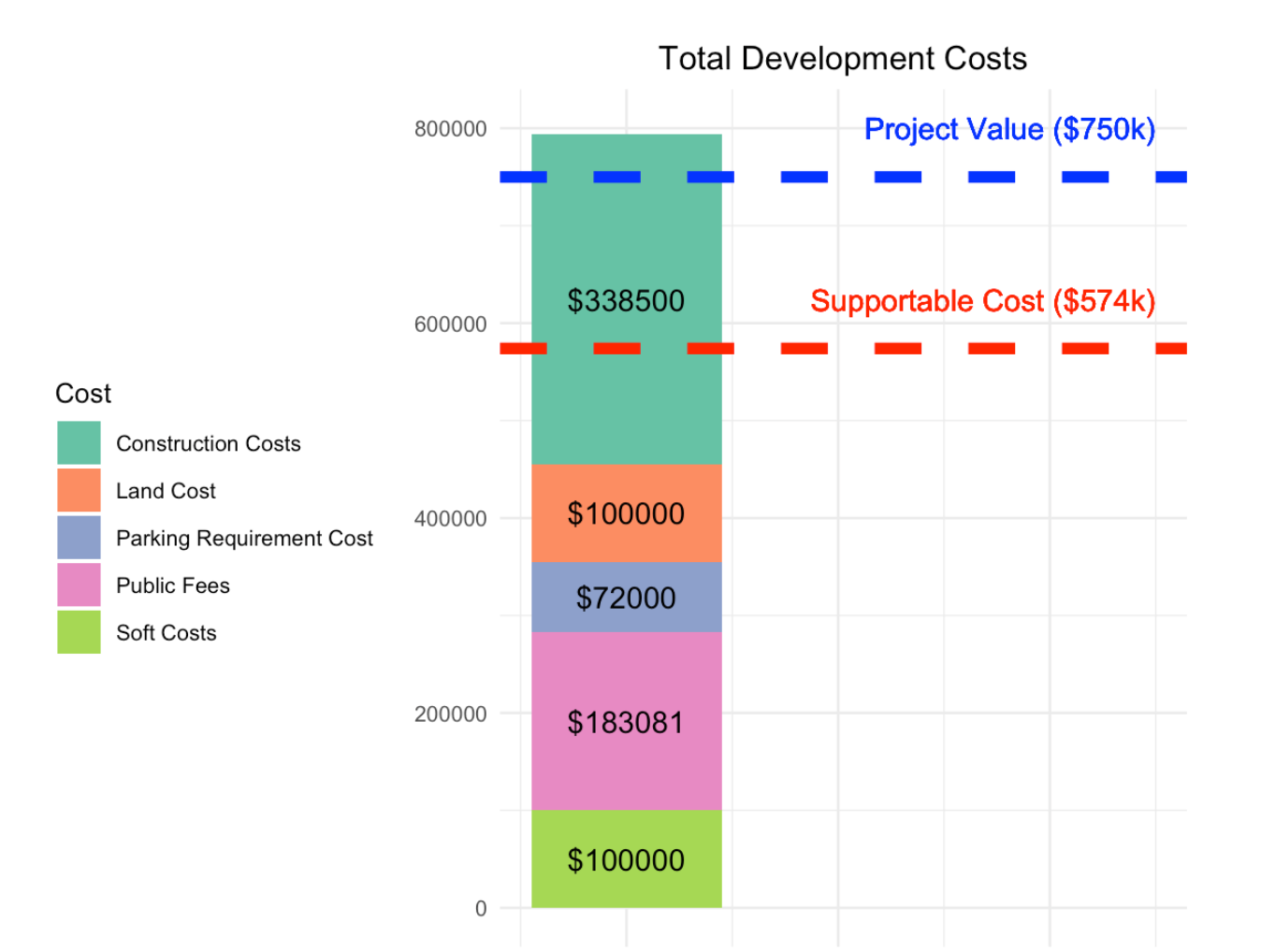

In this section we detail the various constraints to housing production in Mountain View based on the city’s own Draft Housing Element Appendix H and the 2019 East Whisman Precise Plan housing development feasibility analysis by Seifel13. We provide an overview graph followed by an explanation of the impact of each constraint.

The following graph shows that the overall cost of developing a unit of housing is currently $220,000 more expensive than the Supportable Cost, the threshold for economic feasibility.

Methodology

- Seifel calculated the Market Value of an average 800 sqft residential unit to be $750k and the Supportable Cost to be $574k based on an assumption of city-wide $4k monthly rent, 4.25% capitalization rate and 5.25% yield on cost.

- Seifel approximated construction costs of such a unit with 1.025 parking spaces to be $400k. Assuming a $60k / parking spot construction cost, this suggests the unit itself costs $338,500 to build. This allows us to separately highlight the relative impact of city-wide parking requirements.

- Seifel approximates an additional $100k of soft costs mainly related to financial payments during the permitting process.

- Seifel approximates a $100k per unit land cost given the EWPP allowed densities. This will be higher in other parts of the city where the allowed density is lower and can be lower for any project with higher allowed density.

- Seifel had originally approximated city fees to total $100k. We have re-calculated this amount based on the values provided in Draft Housing Element Appendix H Exhibit 2 to be $183,081. This total does not include the following rows:

- Schools - Additional annual assessments or taxes (only applied to North Bayshore Precise Plan area, and only if the School District successfully gets their Mello Roos tax passed by voters)

- Development Requirements - Increased Parking Requirements (increase of .4 spaces per unit) which we are separately calculating at a 1.2 spaces / unit rate.

- Development Requirements - Extended Development Schedule Increased development costs due to delays in City approval. We assume Seifel’s “Soft Costs” analysis already approximates and includes this impact.

- Below Market Rate (BMR) in-lieu fees The On-Site Inclusionary Housing Requirements and BMR in-lieu Fee is approximately 9% of the total development cost for multifamily units (Appendix H, Draft Housing Element). This requirement and the corresponding fee is the city’s main avenue for providing Affordable Housing (AH) and meeting our BMR RHNA allocation. As such, the city should ensure that on-site Inclusionary Housing Requirements and BMR in-lieu fees are set such that they result in the maximum total Affordable Housing units built. A high fee discouraging market-rate development can lead to fewer total AH units than a lower fee. Put simply, if the BMR requirement causes zero market-rate units to be built, then the city will get zero overall BMR units as well.

The draft housing element discounted the possibility that the BMR in-lieu fee could pose a constraint on housing because the goal of producing BMR units is a worthy goal. The goal is indeed worthy, but we challenge the draft’s unfounded assumption that imposing, in the draft’s words, a ‘Major’ ‘Constraint Based on Cost Evaluation’ for market rate units actually does maximize the number of below market rate units built.14 The city should study readjusting this in-lieu fee and/or on-site inclusionary requirement so that the city can maximize the number of below market rate units built citywide.

- Park in-lieu fees The Park Land Dedication (PLD) requirement is the most expensive city-imposed impact fee at about 6-8.5% of the total development cost for multifamily units (Appendix H, Draft Housing Element). The fee is based on the fair market rate for a plot of land for a similarly dense project (Municipal Code 41.41.8) rather than the fair market rate of the surrounding area or of the average parcel in the city, which sets the fee higher than what is necessary for the city to purchase land for a park. As this value is used with no other modifications, the Park Land Dedication in-lieu fees are much higher than neighboring jurisdictions (see table below). While there is an exemption tfor 100% affordable housing projects but not on density-bonus units, this per-unit fee in general drives up costs of every other project, heavily impacting the feasibility of producing housing for persons of low and moderate income under the Least Cost Zoning Law.

The program proposed to address this fee (1.10) incorporates existing council direction from 2019 to review 3 portions of the Park Land Dedication: what parks the fee can pay for, what the land dedication per 1000 residents should be, and revisiting what the categories of the fees are (2021 Staff Report on PLD changes). The first has no impact on the value of the fee, and the second is likely going to raise the cost of the fee since the city is already at the minimum 3 acres/1000 resident target to allow the Quimby Act to be used (2019 Staff Report). The third may reduce fees depending on how the new categorization and recalculation of person per unit (or per bedroom as staff proposed) goes, but it is currently unclear to what magnitude. The most recent update (May 10, 2022) of the Park and Recreation Strategic Plan that directs the PLD revisions makes no mention of the PLD’s impact on development.

| For Multifamily | Per Unit Fee | Per Land Sq Ft Fee |

| Mountain View | $57,000-73,200 (Scenario 1: Most Projects) | $120-280 (By Density) |

| San Jose | $8,000-41,600 | $26-136 (By Location) |

| Santa Clara | $110-137 (By Location) | |

| Palo Alto | $47,892.56 | |

| Sunnyvale | $160 | |

| Los Altos | $48,800 |

Additionally, the city assumes the entire Park Land Dedication requirement is within the Quimby Act (City MFA Annual Report), but the Mitigation Fee Act should apply to the section imposing the requirement on single-lot projects that do not undergo subdivision.

Parking minima The parking cost impact cited in Draft Housing Element Appendix H Exhibit 2 is for a 0.4 space / unit adjustment. Most of the city is subject to a 2 space / unit parking mandate, which would imply that the existing parking requirements represent 9-14% of per unit development costs, surpassing the biggest “Major” impact constraint which are BMR in-lieu fees. The requirement for multifamily projects is closer to 1.2 spaces / unit which is still over 8% of per unit costs.

Permitting delays Some highlights from our prior letter to the city regarding Governmental Constraints to housing production:

Compared to the previous Housing Element, processing times have doubled for many types of projects15,16. This is a particular problem for Precise Plan areas. Despite the great effort already expended in developing the Precise Plans, developments in these areas take just as long to review as equivalent developments outside of Precise Plans17.

Lack of by-right capacity in the city’s zoning means many projects need to apply for a zone change or General Plan amendment (GPA). These projects also need to do an Environmental Impact Report EIR which can take up to 24 months.18

Despite typical processing times of 12-24 months19, the city’s analysis of governmental constraints only considers “Schedule extended by 4 months” which it deduces to be an impact equivalent to 1% of total development cost20. A more accurate impact assessment is an impact of 3-6% of total development costs which is “Moderate to Major” impact by the city’s own definition.

Program 4.1 c) “Acquire tools and software that will improve development review, monitoring of housing supply, management of funding, and other processes involved in housing development for staff and public use.” is the only proposed program relating to this constraint, and we believe it will not be sufficient as there’s no new software the city can adopt to reduce the 12-24 month EIR requirement for GPA projects or make the “discretionary” aspect of EWPP and NBSPP projects unnecessary. These issues need to be addressed at the zoning level.

- Staff capacity Overall, lack of financially feasible by-right capacity in the city’s zoning makes the city staff capacity a bottleneck to housing production in Mountain View. This, and the “Permitting Delays” from earlier are very closely related.

Exhibit 1 Use of the city’s Bonus FAR program is a necessity by design in key Precise Plan areas due to purposely low base FAR21. This means a lengthy discretionary process with more staff involvement than a by-right process or one that doesn’t involve a discretionary “community benefit” criterion.

Exhibit 2 If a project requires a zone change or General Plan amendment, the City Council first considers a “gatekeeper” request which is a lengthy process. Due to Mountain View’s current zoning, very few by-right zoning compliant multifamily projects produce enough economic incentive for developers. As such, projects tend to opt for a “gatekeeper” process. Unfortunately the city is not considering any new “gatekeeper” projects due to lack of staff capacity until 2024.

The draft does not clearly call out this bottleneck as a constraint to housing development. There is no analysis of the expected number of units produced per hour of staff’s time or the overall capacity of the current staffing. That means there’s no comparison of “hours it takes to approve applications needed to satisfy the city’s RHNA allocation” versus “what the city has capacity to approve”. Program 4.1 c) “Acquire tools and software that will improve development review, monitoring of housing supply, management of funding, and other processes involved in housing development for staff and public use.” is the only proposed program relating to this constraint, and we believe it will not be sufficient.

Furthermore, as we described in our prior letter, staffing levels are exceptionally low, creating a taxing workload for staff.22 In addition to being a constraint to development, low staff levels also prevent the city from taking on programs to AFFH, as was evident in the March 8, 2022 city council study session where city staff cautioned the city council that adding programs to the housing element would cause other city priorities to be deprioritized due to staff bandwidth issues.

- Development guidelines As the Draft correctly recognizes, State law requires the City to evaluate “[u]nderutilized sites that are… capable of being developed at a higher density.”23

Accordingly in the fifth cycle, the City had a program to “[m]onitor the supply of underutilized sites … to ensure opportunities are available” for “a variety of housing types.”24 This program, which the City calls “[o]ngoing” (ibid.), purportedly includes “reviewing the R3 (Multifamily Residential) zoning standards.” (Ibid.)

In 2020, the City Council commissioned an Opticos study on “constraints for producing new stacked-flat multi-family housing in the R3 Zone.” (Alkire & Shrivastava, R3 Zoning District Update, p. 2.) On October 13 of that year, Opticos presented five key findings to the Council:25

- Allowed Density too low

- Allowed Height too low

- Setbacks, Lot Coverage, and FAR Limit Development

- Parking Requirements are too high

- Open Space requirement too high

(Opticos, Key Findings and Observations, pp. 7-11.) These constraints “limit the feasibility of new development” (Alkire & Shrivastava, supra, at p. 7), requiring a new approach to multifamily design restrictions in Mountain View.

So far, Mountain View has ignored Opticos’s findings. The Draft claims that “[t]he City is currently updating the R3 zoning district development standards to … incentivize stacked-flat development” (Draft, p. 177), but fails to commit to any specific reform. Worse, the City may abandon its “underutilized sites” program entirely. (Compare _id. _at p. 30 with id. at pp. 14-25.) In its new programs, the most the city commits to do is “[u]pdate” zoning “as needed” and address other constraints “as necessary” by “[c]omplet[ing] a review of development standards” that “could” include “open area, parking … and other standards” that “may” constrain development. (Id. at p. 14.) As just shown, the city _has _reviewed its development standards and _knows _what constrains development. The draft should commit to removing these constraints.

G. AFFH Implications

The fees we impose on new development of multifamily residential are wildly inequitable. As we’ve already shown, vulnerable populations in Mountain View overwhelmingly live in the highest density residential units available. Mountain View’s public fees are structured to target these exact types of developments, driving up the cost of their construction, and thereby raising the rents the eventual residents will pay. These fees then go back to the city to support amenities that are enjoyed by homeowners in R1 zones who are exempt from many of these fees.

Furthermore, we will not be able to accommodate multifamily housing in high opportunity areas if it remains economically infeasible to build multifamily housing. Thus, the city’s ability to resolve the economic infeasibility of multifamily housing acts as a side-constraint to the city’s ability to undo patterns of socioeconomic segregation in the city.

Currently, the city addresses this economic feasibility gap with office-housing linkages and bonus office FAR for multifamily projects in certain precise plans. In effect, new office development subsidizes the cost of building housing in East Whisman, as was described in Mountain View Voice’s 2022 article entitled “Mountain View approves fees on housing already considered too costly to build.”26 The same is true for the North Bayshore Master Plan, which the housing element draft fails to note is primarily an office development project from Google’s economic point of view. Without the office, there is no housing.

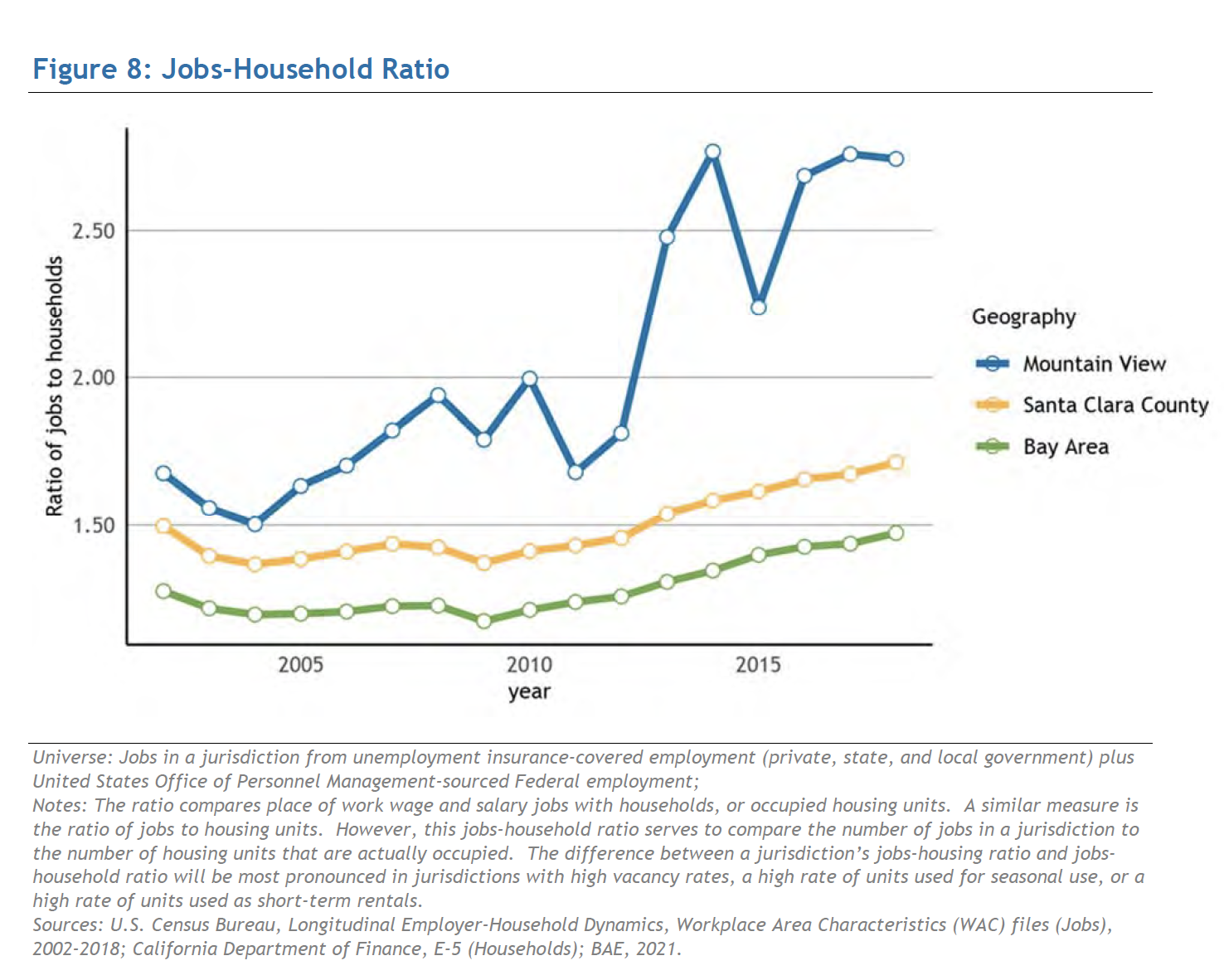

Because housing is infeasible to build without office development to subsidize it, the result of this decades-long strategy is that the city’s jobs-housing imbalance continues to grow, with additional displacement pressures for renters.27 This is not just a local AFFH issue, but a regional one, as our jobs-housing imbalance creates supercommuters and displacement pressures in other Santa Clara County communities. To resolve this issue, the city should make housing feasible to build without needing to rely on office construction.

Footnotes

We appreciate the city’s willingness to acknowledge outside of the draft that these regulations are all constraints to some degree, but this language should be included in the draft. ↩︎

As required in 24 CFR § 5.158, Community Participation means a solicitation of views and recommendations from members of the community and other interested parties, a consideration of the views and recommendations received, and a process for incorporating such views and recommendations into decisions and outcomes. To address these requirements, the housing element must describe meaningful, frequent, and ongoing public participation with key stakeholders. ↩︎

Gov. Code, §§ 65583, subds. (c)(9), (c)(10)(A)(i), 8899.50, subds. (a), (b), (c); see also AFFH Final Rule and Commentary (AFFH Rule), 80 Fed. Reg. 42271, 42353-42360 (esp. 42354-42356), 42363-42364 (July 16, 2015). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CFR-2016-title24-vol1/CFR-2016-title24-vol1-sec5-158 ↩︎

See, e.g. Table 28 of the draft Housing Element, showing that homeownership rates in the local Hispanic/Latino population at 20.5%, with city-wide homeownership rates at 41.6%. ↩︎

See the HCD guidance, https://www.hcd.ca.gov/community-development/affh/docs/affh_document_final_4-27-2021.pdf ↩︎

There are multiple ways clustering could be measured. This is intended as a measure to prevent focusing multi-family developments along highways/other corridors that may experience disproportionate air/noise pollution. ↩︎

Mountain View is part of the Mountain View-Los Altos High School district. Many students in Mountain View attend Los Altos High School instead, which has similar issues with regards to its nearby land-use patterns. ↩︎

Note that some of the concerns about housing near roadways—particularly noise pollution—do also apply to the areas around the Caltrain line. However, there are in-progress efforts to electrify Caltrain (removing diesel pollution from the main rail line), as well as to grade-separate the rail crossings (reducing noise pollution from horn usage). There are no comparable efforts underway to reduce air or noise pollution from major arterials to the same degree, beyond long-term goals of increased fleet electrification (which will address some air pollution concerns, but will not fully address particulate emissions from tire degradation, brake dust, or roadway wear). ↩︎

As has been the topic of discussion at multiple recent hearings related to individual housing projects, there are significant increases in air pollution in the few hundred feet nearest major roadways. See, e.g., https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK361807/ for some discussion. ↩︎

See this convenient map of transportation-related noise pollution from the US DOT: https://maps.dot.gov/BTS/NationalTransportationNoiseMap/ ↩︎

See Figure 1, from http://mountainview.legistar.com/gateway.aspx?M=F&ID=6ef488ce-9bfa-49dd-bd8b-ad6bda80068b.pdf for a map of Mountain View’s high-injury network. ↩︎

“Council greenlights 716 apartments, teacher housing”, Mountain View Voice, October 24, 2018 https://www.mv-voice.com/news/2018/10/24/council-greenlights-716-apartments-teacher-housing ↩︎

ATT 7 - Resolution - Community Benefits.pdf - Seifel Consulting Inc Memorandum ↩︎

See Exhibit 2 entitled “Summary Financial Evaluation of Governmental Constraints Based on Cost Impact Per Housing Unit Mountain View Housing Element Governmental Constraints Analysis” in the final appendix of the draft housing element. ↩︎

City of Mountain View, 2015-2023 Housing Element, Tables 6-3 and 6-4 ↩︎

Draft, Table 36 ↩︎

ibid. ↩︎

Draft, p192 ↩︎

Draft, Table 36 ↩︎

Draft, Appendix H, Exhibit 2 ↩︎

Draft, Table 35. Base residential FAR is only 1.0 in the North Bayshore and East Whisman PP areas, and 1.35 in the El Camino Real and San Antonio PP. ↩︎

https://mvyimby.com/post/2022-06-10-housing-constraints-council/ ↩︎

See page 213 of the draft housing element. ↩︎

See page 30 of the draft housing element. ↩︎

R3 Zoning District Update - Study Session Documents, ATT 2 - R3 Key Findings and Observations ↩︎

https://www.mv-voice.com/news/2022/05/25/mountain-view-approves-fees-on-housing-already-considered-too-costly-to-build ↩︎

See page 53 of the draft housing element ↩︎